While alive, you can donate one kidney, part of your liver, and certain other organs and tissues.

You can donate a kidney, a piece of your liver, and certain other organs and tissues while alive. About 6,500 living donation transplants take place each year.

Unlike deceased donors, a living donor can decide who to donate their organ to, helping a recipient get an organ transplant faster. Most living donations happen between family members or close friends. Other people choose to donate to someone they don't know. See stories of real people who have donated and received organs.

Living donation is typically safe for the donor. Most living donors go on to live active, healthy lives and can see the positive impact of their donation.

85% of people on the organ transplant waiting list need a kidney.

Benefits of living donation

- As a living donor, you can choose who receives your organ.

- You can reduce someone’s waiting time for an organ transplant.

- Living kidney donation can prevent—or shorten—the need for kidney dialysis.

- Research has shown that recipients of organs from living donors have better outcomes than those who receive organs from deceased donors.

Kidneys are the organs most frequently needed, followed by livers. Both of these organs can be donated by living donors to save someone’s life.

You may be able to donate:

- One kidney

85% of people awaiting a transplant need a kidney. A kidney is the most commonly donated organ. Your remaining kidney removes waste from the body. - Segment of the liver

Remaining liver cells grow or refresh until your liver is almost its original size. This happens in a short amount of time for both you and the recipient. - One lobe of the lung, part of the pancreas, or part of the intestine

These donations are rare. While these organs don’t regrow, the portion you donate and the portion that remains can function fully.

You may be able to donate:

- Skin—after surgeries such as a tummy tuck

- Bone—after knee and hip replacements

- Healthy cells from bone marrow and umbilical cord blood

- Amnion—donated after childbirth

- Blood—white and red blood cells—and platelets

You can donate blood or bone marrow more than once. The body replaces them after you donate.

Understanding living donation

- Most living donors go on to live healthy and active lives.

- Most living donors report living donation as a positive emotional experience.

- Living donors tend to have similar or better quality of life than before the donation.

Parents, husbands, wives, friends, co-workers—even total strangers—can be living donor candidates.

To be a living donor, you must:

- Be at least 18 or older (some transplant hospitals require donors to be at least 21)

- Have good physical and mental health

- Know the risks and benefits of living donation

- Make an informed decision that living donation is right for you

Both you and the transplant hospital staff will need to decide whether living donation is right for you. Hospital staff will gather a lot of information about you to determine if you are healthy enough to donate an organ.

You can expect to:

- Complete a physical exam, lab tests, and screenings for cancer and other conditions

- Answer questions about your medical history

- Receive a mental health evaluation

- Answer questions about your social support

- Discuss your financial situation and whether you can take time off from work or any caregiving responsibilities

- Learn about the risks and benefits of living donation

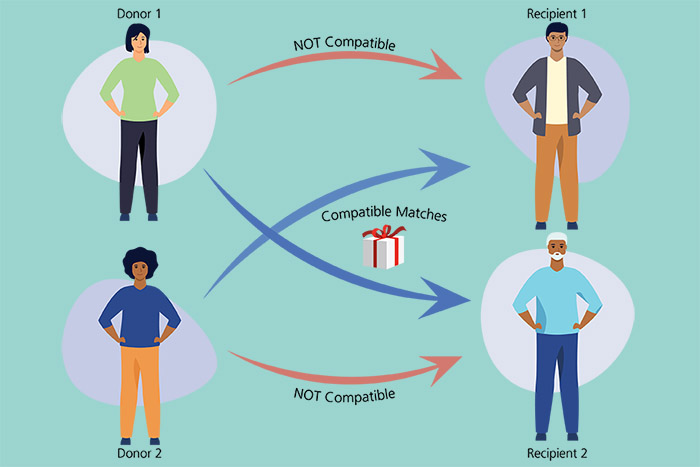

If tests show that you are not compatible with the person in need of an organ transplant, you may have other options to donate, such as kidney paired donation.

- Surgery takes place at a transplant hospital.

- Living kidney donors typically stay two to three days in the hospital; liver donors can expect about a five-day stay.

- Living donors resume normal activities after donation recovery, which takes about six to twelve weeks when donating a kidney and about eight to twelve weeks when donating part of the liver.

For more information about the living donation process, visit the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network's living donation page.

Transplant centers follow-up with living donors after the transplant. They report, on average, living donors do well over the long term.

As with most medical procedures, there are possible risks for living organ donation surgery. These risks differ depending on each individual donor as well as the type of organ donated. Short-term effects may include pain or infection from the procedure. Long-term effects can include hypertension for kidney donors, or intestinal problems for liver donors.

As more research emerges on the impact of donation on living donors, the more we can fully understand the risks and benefits to living donors.

What to think about before you donate

- Recovery from surgery takes time, and donors may have to take off work and stop certain activities for a while.

- Living donors do not have to pay for medical costs because the recipient’s insurance usually covers expenses.

- You may experience medical problems that delay your return to work.

- You may face lost wages from being out of work, or incur additional costs for childcare or other expenses, depending on your situation.

- Some living donors have had problems keeping insurance coverage at the same level and rate.

It can be very rewarding to help another person. You can donate an organ to someone you know (directed donation) or to someone you don’t know (non-directed donation). If you wish to help someone through directed donation but you are not a match, kidney paired donation may be an option.

Kidney paired donation allows for two or more incompatible donor/recipient pairs to swap donors. The donors are then able to give their kidney to a compatible recipient in a different pair. By exchanging donors, a compatible match can be found for these recipients.

HRSA’s Living Organ Donation Reimbursement Program reimburses up to $6,000 of a living donor’s expenses if the donor cannot reasonably expect coverage from their insurance, the recipient, or other programs. These expenses may include:

- Travel, lodging, and meals,

- Lost wages

- Childcare and eldercare costs related to the donor’s evaluation, surgery, and follow-up visits

To be eligible for reimbursement:

- The donor and recipient must both be U.S. citizens or lawfully present residents.

- The donor’s application for reimbursement must be submitted and approved before the transplant surgery.

- Household income may determine eligibility for reimbursement.

Non-directed living donors who give an organ (e.g., a kidney or a portion of their liver) qualify for reimbursement as long as they meet the citizenship and residency requirements.

Learn more about HRSA’s Living Organ Donation Reimbursement Program, including the full eligibility guidelines and types of expenses that can be reimbursed.

Apply for reimbursement at livingdonorassistance.org.

You can learn more by contacting the patient services department of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) at 1-888-894-6361 or email Patient.Services@unos.org.

Visit the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) site on living donation.

A next step

If you would like to help someone you know through living directed donation, talk to them and contact the transplant program where the person is listed. If you would like to help someone you do not know by being a living non-directed donor, contact a transplant hospital of your choice and ask if they have such a donation program. Go to the OPTN Member Directory for a list of transplant hospitals.

View or download English and Spanish educational materials on living organ donation, including videos, an infographic, social media graphics, and fact sheets for potential donors and recipients.